TriplePundit • New Satellite Network Seeks to Give Wildfire Responders an Edge With Ultra-Precise Early Detection

Wildfires are becoming more common, more intense and more costly. A new satellite program called FireSat aims to spot them when they’re still small so fire crews and communities can respond sooner.

“First, we want to transform global understanding of wildland fire, including the many fires that are natural and beneficial,” said Brian Collins, executive director of Earth Fire Alliance, the nonprofit leading the effort alongside partners in tech, science and philanthropy. “Second, we want to arm communities to make better decisions during high-intensity, fast-moving events.”

The idea for FireSat came together a little over four years ago, even before the Earth Fire Alliance formally existed. At the same time Google Research was exploring how data and artificial intelligence could be applied to wildfire detection, organizations like the Environmental Defense Fund, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the Minderoo Foundation were asking whether a collection of satellites could improve wildfire resilience. These efforts converged around a study to test whether satellites could truly improve global wildfire awareness and response, Collins said.

“Existing systems were mostly large, government satellites designed to handle many missions … They can detect fires, but wildfire isn’t their singular focus,” Collins said. “The pathfinder for our approach was MethaneSAT, which showed that a community can build a purpose-built, philanthropy-backed mission with global impact. That success suggested we could do the same for wildland fire.” Launched by a group of researchers, tech companies, and science organizations, the MethaneSAT satellite measures methane emissions, including some that were once untraceable, with exceptional precision. It’s data is publicly available.

The sensors on FireSat satellites features ultra-sensitive thermal infrared bands that are tuned to detect tiny heat signatures, and its filters screen out false alarms. “Sensitivity without discrimination would send crews on wild-goose chases. Discrimination without sensitivity would miss fires,” Collins said. “FireSat is designed to do both.”

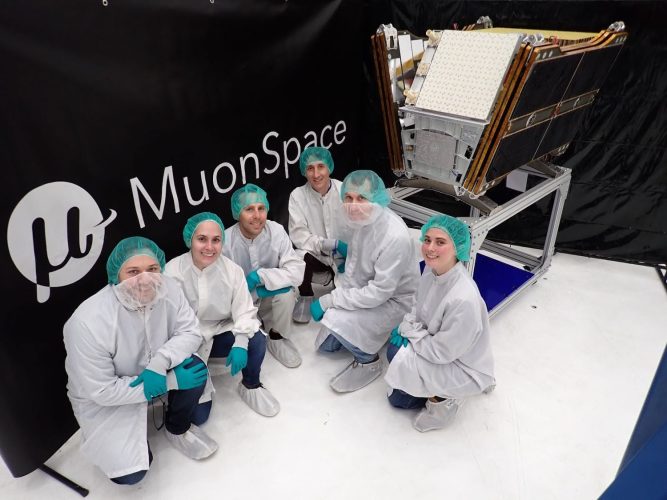

Currently, NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites give scientists global coverage of what’s happening on Earth twice a day. That means a wildfire spotted in the morning can be checked again a few hours later to see how it’s spreading. The first FireSat spacecraft — called the Protoflight and created by space systems provider Muon Space — launched in March and currently circles Earth every 90 minutes, viewing each point on the globe twice per day. The next three satellites to launch will operate in a similar manner.

When the full FireSat system of about 52 satellites is in place, the average time it takes before a satellite passes over the same place again will shrink to 20 minutes. “We didn’t pull that number out of thin air,” Collins said. “After a lot of user engagement with agencies around the world, we found 20 minutes was the knee in the curve: fast enough to materially improve [wildfire] suppression options and enable timely public warnings and evacuations.”

Managing the torrent of data sent from the satellites is the next challenge. Even a single spacecraft produces a flood of pixels that must be processed rapidly into useful information. FireSat’s team is working with artificial intelligence researchers, data scientists, and fire-modeling experts to accelerate that pipeline.

“If you ask what keeps me up at night, it’s this,” Collins said. “We launch the satellites, we’re producing data, and no one is ready to make a better decision using it.”

Earth Fire Alliance has held a series of workshops with the Environmental Defense Fund to discuss implementation, and an early adopter program gives agencies and researchers hands-on access to products from the Protoflight satellite, Collins said. Because wildfires are local events, and readiness to use new data varies worldwide, building an alliance that connects similar fire regimes — such as Mediterranean shrublands in California, Portugal and Spain; conifer forests in the American West; peat fires in Indonesia; and land-use fires in Amazonia — is important.

“We don’t want a one-size-fits-all ‘bang detector’ for megafires in the Western United States,” Collins said. “We want something useful in every region.”

That feedback loop is already paying off, Collins said. One fire department used FireSat data to view and distinguish between an active fire and a five-year-old burn scar in the same image, helping them place resources to address the new fire. In another instance, FireSat picked up roadside ignitions in grasslands that were less than a half acre in size — fires so small many departments never expected satellites to see them. “Those departments are now preparing to integrate detections they previously ignored,” Collins said.

Catching small fires early is fundamental. Low-intensity burns are part of many ecosystems, but they often go unobserved, Collins said. By seeing them consistently from space, FireSat can help scientists map biodiversity impacts and give responders more lead time.

“It’s much easier to suppress a small fire than a big one, and it’s much easier to warn a community before that small fire rushes into their neighborhood,” Collins said. “Detecting fires earlier can prevent extreme growth and reduce smoke exposure … Measuring fire intensity can support future strategies that manage — not only suppress — fires to reduce health impacts. For firefighter safety, persistent, wide-area awareness helps crews understand what’s ‘over the hill,’ especially for rural departments without aircraft or dense camera networks.”

Beyond response, FireSat can also aid triage when multiple fires are burning. By estimating intensity, mapping fuels, and showing recent burn areas, the system can point crews toward the greatest risks. Better decisions can translate to lower damage and lower costs, Collins said.

Access is a priority. FireSat plans to prioritize first responders, scientists, and the public through agencies and nonprofit or commercial alerting platforms. International collaboration will also be key as the number of FireSat satellites grows toward its full strength leading up to 2030. “Collaboration ensures the system serves diverse needs and enables locally appropriate strategies,” Collins said.

Ultimately, Collins hopes FireSat helps people think about fire the way Gulf Coast residents think about hurricanes: being informed, vigilant and ready to act. Increased public awareness, paired with earlier detection, faster data, and better coordination, could reshape wildfire response and climate resilience.

“With modern sensing, we can monitor precursors — fuel, moisture, heat, ignition, storm formation — share risk information, and act earlier,” Collins said. “That ultimately gives communities more control in a changing climate.”

Post Comment